Bottom line: Yes, it could. As of today, June 30, 2014, land within Madison and Oneida counties (just east of Syracuse) that is owned by the Oneida Indian Nation becomes eligible for conversion to federal "Trust" land and subject to Bureau of Land Management rules. According to Bureau of Indian Affairs spokesperson Nedra Darling, “As of June 30, the Department of the Interior will take the land into trust at a time of its choosing.” The change comes as a result of a settlement deal brokered by Cuomo and Oneida Indian Nation Representative and CEO, Ray Halbritter. This settlement is a casino deal, but one with implications that concern fractivists.

Because federal land is not subject to state or local law, under Obama's "All of the Above" energy policy, the change could open the door to fracking within New York State, despite a de facto moratorium.

Background on the Settlement

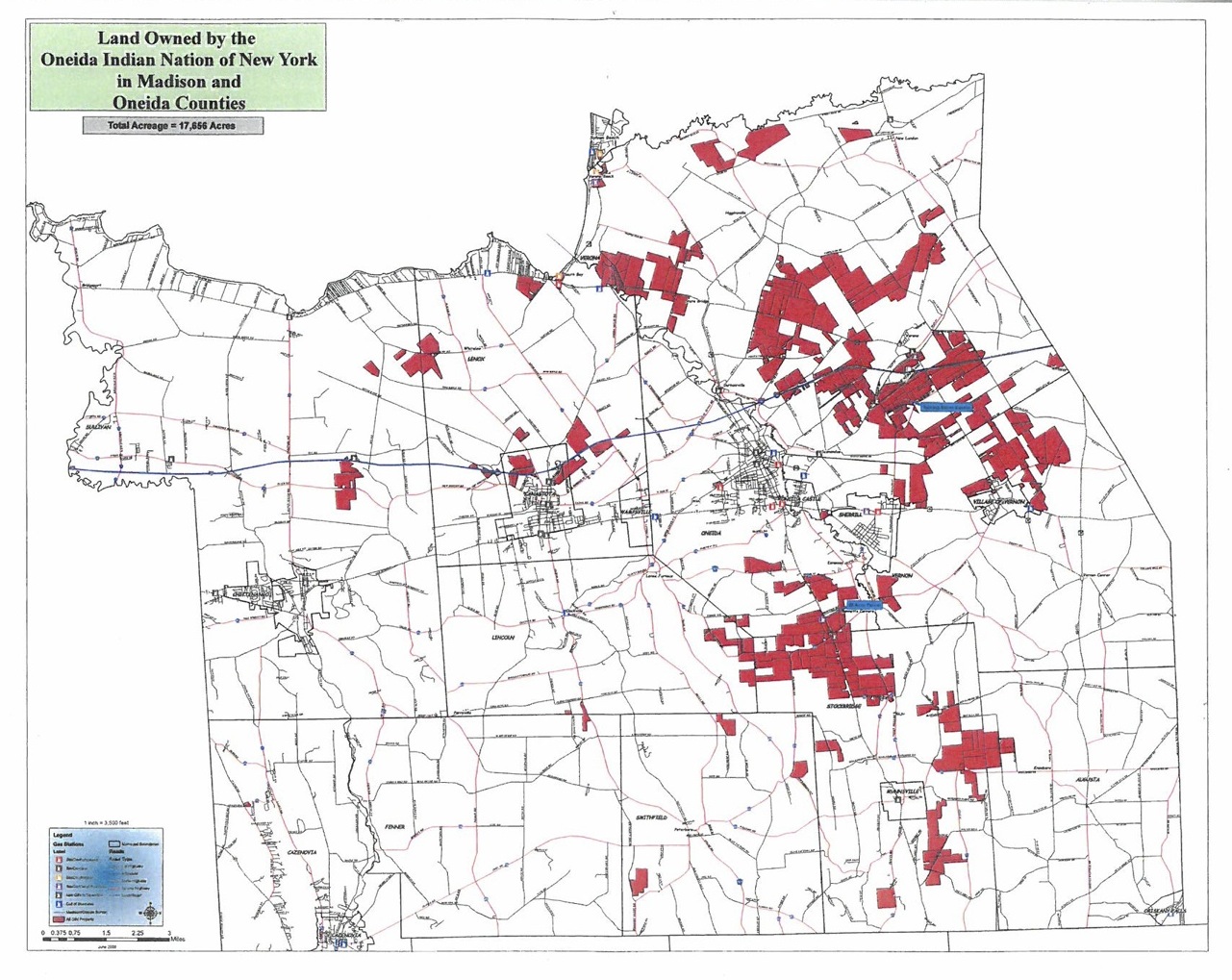

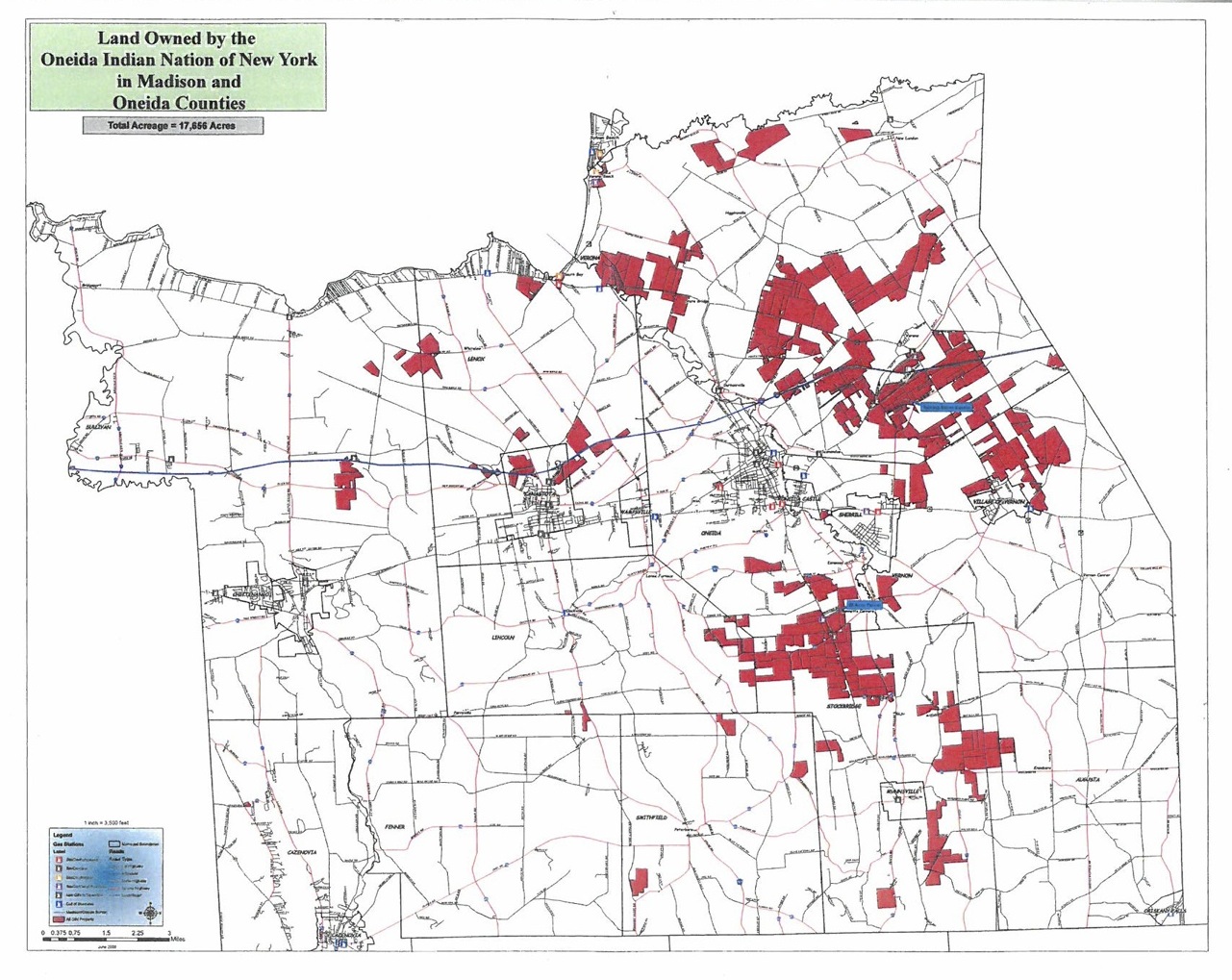

More than fifty five million acres nationally are held in federal trust. The Oneida Nation is considered a leader in the movement among tribes to buy back and federalize their lands. Starting in the 1990s, using profits from their Turning Stone casino, the Oneida Nation began buying parcels (about thirteen thousand acres) scattered within Madison and Oneida counties, asserting that once they owned it, those parcels would be tax exempt. The tribe wanted to avoid local and state taxes on cigarette and gasoline sales and casino profits. The state brought a lawsuit to prevent that, and while the state won the suit, the case opened the door for the Oneidas to escape taxation by putting the lands into trust. In September 2009, U.S. District Judge Lawrence Kahn ruled that placing the land into trust is constitutional.

Signed by Cuomo and Halbritter in May of 2013, the agreement intends to resolve litigation going back to 1970, over back taxes totaling approximately $800 million. The agreement grants the Oneida Nation exclusive gaming rights in ten counties, with a portion of the revenues generated to go to state and local governments. Payments would equal approximately $50 million annually. The agreement also grants the Oneida Nation sovereign control of up to 25,000 acres (they currently hold a little less than 18,000 acres).

The towns of Vernon and Verona are challenging the settlement. But new federal rules allow the transfer of land into trust while litigation is pending. It seems a long shot that the lawsuits might hold up the transfer, and there appears to be no injunction option that meets the necessary legal standard of "immediate and irreparable harm."

Several local representatives have praised the deal, including State Senators Griffo and Velesky, and Assembly Members Blankenbush and Brindisi. But not all officials are happy about the deal: Syracuse.com reported that John Becker, Chair of the Madison County Board of Supervisors, fought back tears as he "told colleagues he doesn't like the agreement but felt he had no choice but to vote yes." Assembly Member Claudia Tenny, a Republican gun advocate and opponent of gay marriage, opposes the deal and suggested that Cuomo was "ramrodding another thing through," noting the deal would create a devastating and permanent loss of sales and real estate tax for localities.

Concerns Stoked by the Deal

The agreement has raised concerns for residents in Madison and Oneida counties, ranging from loss of tax revenue to logistics such as who will control snow plowing, building code and law enforcement, and the question of fracking. Remembering Cuomo's suggestion that the Southern Tier be used as a test case, some believe that opening the state to fracking is a hidden motivation behind the deal. Others maintain there is no hidden agenda and point out that negotiations have been going on since before fracking was an issue.

Sane Energy Project has looked into those concerns related to fracking, such as:

A lack of transparency

While following this story for more than a year, we've found much of the surrounding background to the deal nearly impenetrable. The situation is a hornet's nest of long-running lawsuits, back taxes and accusations from all sides. Few citizens are well-informed about the details, and even local officials involved in related litigation were unaware that the land was about to be placed into trust, until a local newspaper published the announcement. The deal is not open to public comment of any kind, and is no longer open to legislative action.

Fear of compulsory integration

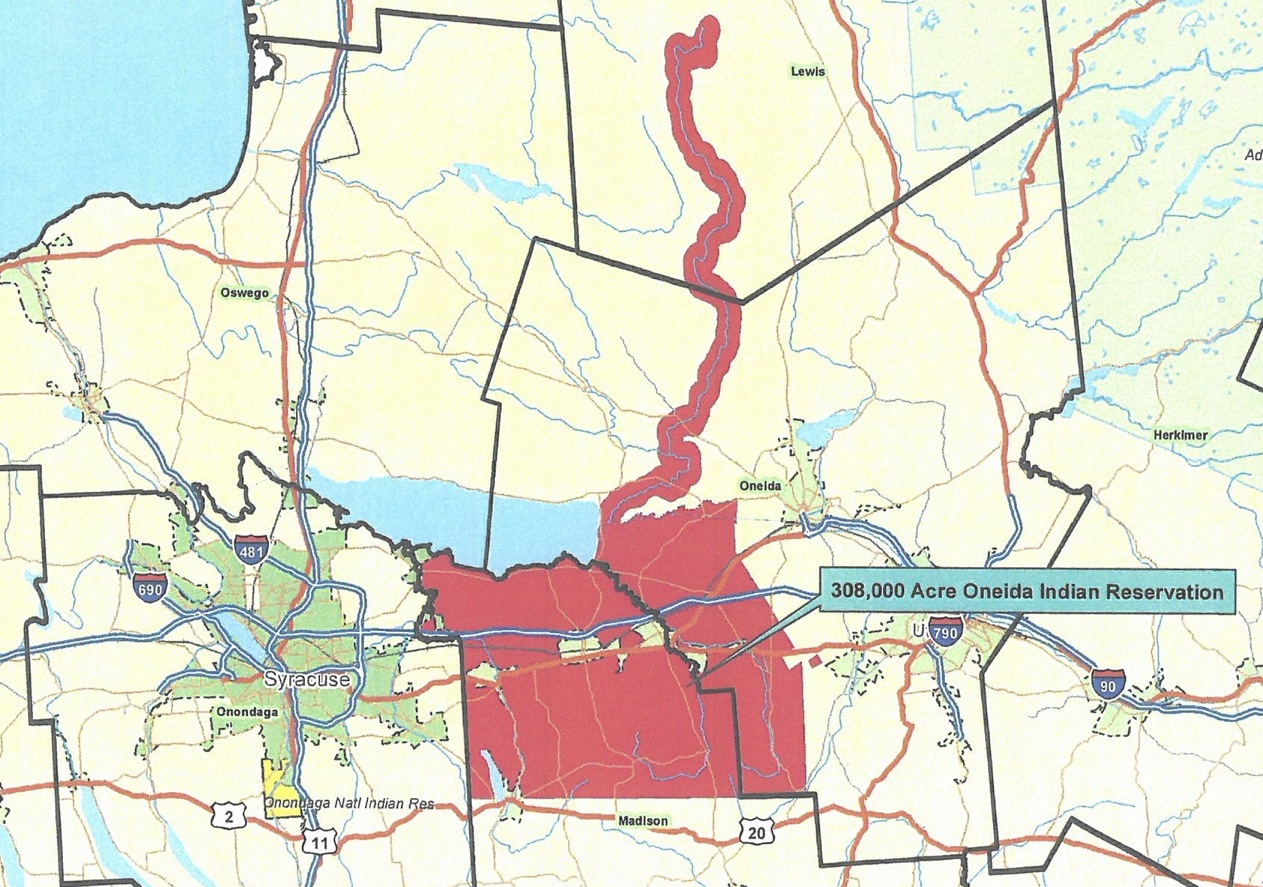

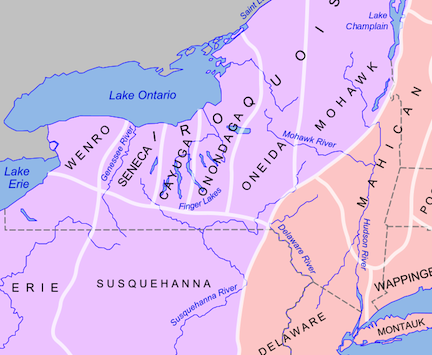

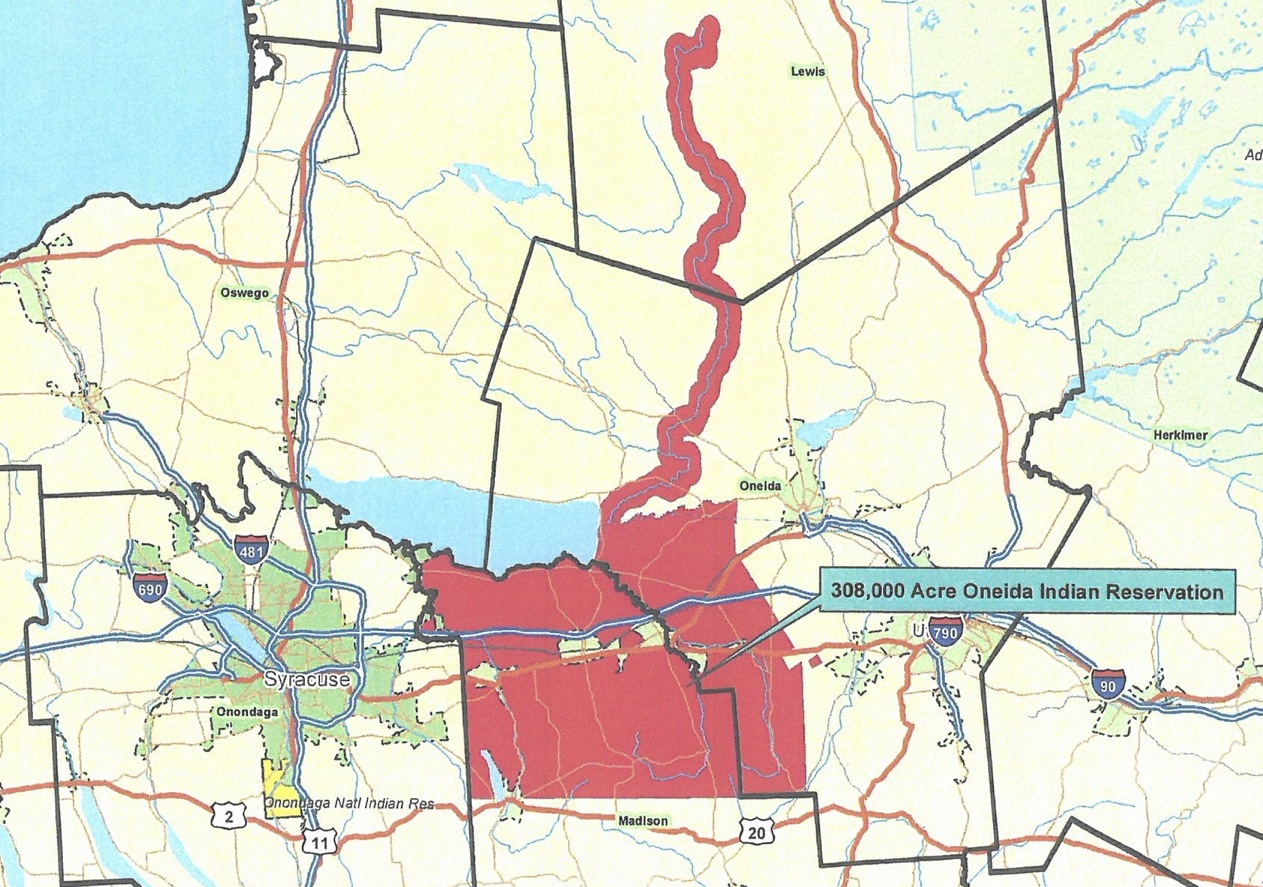

Some local residents worry that the 25,000 acres the deal allows the Oneida Nation to hold in trust will turn into 300,000 acres (the total acreage allotted to the reservation, shown on map at left) and that the privately-held land that lies between the Oneida-owned parcels will essentially be compulsorily integrated. It is unusual for scattered parcels to be taken into trust, something known as "checker boarding," which federal agencies normally avoid. The non-contiguous position of Oneida-held parcels does raise some logistical questions, noted above.

Some local residents worry that the 25,000 acres the deal allows the Oneida Nation to hold in trust will turn into 300,000 acres (the total acreage allotted to the reservation, shown on map at left) and that the privately-held land that lies between the Oneida-owned parcels will essentially be compulsorily integrated. It is unusual for scattered parcels to be taken into trust, something known as "checker boarding," which federal agencies normally avoid. The non-contiguous position of Oneida-held parcels does raise some logistical questions, noted above.

However, our reading of the settlement does not support the suggestion that all 300,000 reservation acres will become federalized: the deal sets a "permanent" cap of 25,000 acres that can be under Oneida sovereign control, which may be taken into trust by the Department of Interior. Under the language in the deal, the Oneidas Nation expressly waives their rights of sovereignty over any land above the cap amount.

On the other hand, since the Oneida Nation is allowed to purchase approximately 7,000 additional acres to take into trust, that does raise the question of where those parcels may fall.

Fear of shale gas development

Some fear that fracking will begin once the lands are taken into trust. However, whether gas will be developed on Oneida land is a complicated question.

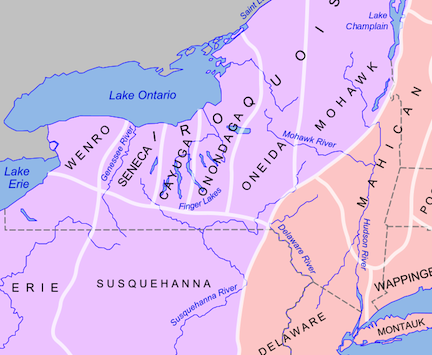

The Oneidas and Onondagas are neighboring members of the Iroquois League. While the Onondagas have demonstrated a clear anti-fracking stance, under Halbritter's leadership, the Oneida Nation appears more open to developing natural gas. The Oneidas have shown interest in drilling on tribal property before, hoping to use the gas to power their casino. Vertical, low-volume drilling has historically been done in the area and, via the firm, Ardent Resources, the Oneida Nation purchased 123 gas leases. However, that was in 2004, well before fracking was on most people's radar, and before the Halliburton Loophole was added to federal energy policy in 2005, a change that removed fracking from oversight within the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, and launched the modern fracking era.

Under the agreement reached with the state, the Oneida Nation retain the rights to their land and any leasing would have to be instigated by them, unlike federal public lands that the Department of the Interior can lease simply with executive approval.

In all likelihood, based on production data of similar shale and sandstone reported by four experts in January of 2014, there's very little gas to be gotten in the area that is being federalized. Reports are that test wells the Oneida Nation had drilled turned out to be duds–consistent with the expert's predictions. However, as the experts also noted, projections of poor production won't stop wildcat drillers from trying, and every well drilled is a potential aquifer contamination.

Fear of frack waste disposal

Possibly more worrisome, the area's geology could prove tempting for injection wells to dispose of frack waste. We know Pennsylvania drillers are desperate for places to unload their flowback and drill cuttings.

The DEC database accounts for 71 old/existing wells in Oneida county and 144 in Madison. In addition to new injection wells being created, old wells could be converted into injection wells. Old wells also make for easy migration of fracking fluids used in new drilling, which can consequentially migrate into aquifers. Any injection wells would have to be approved by the EPA–however, the EPA has no mandated public hearing process for injection wells, and does not post those wells publicly on their website until the applicant has already received a provisional permit.

Some New York landfills along the Pennsylvania border are already accepting frack waste, and because drill cuttings weigh more than municipal waste, it is seen by some cash-strapped towns as more profitable. Some towns also accept frack brine and brine-derived salt for road use. These decisions are hotly debated, and usually made at the town or county level under DEC oversight, but once the lands are federal, disposal on tribal property could happen without public input from neighbors outside Oneida Nation borders.

What Now?

Whatever the intention or history around this deal, the bottom line is: the land will become federal land. It will be exempt from state or local law, and will be open to fracking, and frack waste disposal will no longer be under local control.

For us, watching this situation develop has been akin to realizing your car is sliding off the road on black ice and you can't do a thing to stop it.

We are mightily frustrated but hope that, in the absence of legal options, there may be other means of preventing environmental damage in these counties, hopefully through productive dialogue. Meanwhile, we will continue to monitor the situation carefully.

Some local residents worry that the 25,000 acres the deal allows the Oneida Nation to hold in trust will turn into 300,000 acres (the total acreage allotted to the reservation, shown on map at left) and that the privately-held land that lies between the Oneida-owned parcels will essentially be compulsorily integrated. It is unusual for scattered parcels to be taken into trust, something known as "checker boarding," which federal agencies normally avoid. The non-contiguous position of Oneida-held parcels does raise some logistical questions, noted above.

Some local residents worry that the 25,000 acres the deal allows the Oneida Nation to hold in trust will turn into 300,000 acres (the total acreage allotted to the reservation, shown on map at left) and that the privately-held land that lies between the Oneida-owned parcels will essentially be compulsorily integrated. It is unusual for scattered parcels to be taken into trust, something known as "checker boarding," which federal agencies normally avoid. The non-contiguous position of Oneida-held parcels does raise some logistical questions, noted above.